An aspiring young singer takes the stage. As the music plays, her timid voice begins to soar. The skeptical audience quickly warms to the performance. As luck would have it, a well-known music executive is in the crowd that night. He offers to take her under his wing. She’s been discovered.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the plot from the Academy Award-winning film A Star is Born—a film so popular it has been remade three times. Its appeal is rooted in the classic rags-to-riches story line, a compelling narrative that has been told for centuries in literature, music, and theater. Good stories follow familiar patterns that spark recognition in the audience, with universal themes that are inherently satisfying.

When you write a speech, how do you make it engaging? Professional speechwriters frequently note that storytelling is paramount. But they don’t always say what goes into a good story.

As a lecturer in the strategic communication program at Columbia University in New York, New York, and an independent speech and presentation coach, I find that the elements seen in a strong story arc are also key to persuasive speaking. In Toastmasters, we weave stories—funny, somber, insightful, relatable—into our speeches for the same purpose: to persuade, inform, influence, or inspire.

The impact of a story begins in its bones—the basic structure that supports many varied narratives, such as the rags-to-riches story arc. As you prepare to write your next speech, use these points to perfect your narrative and become a more compelling speaker.

The Hero’s Journey

In his groundbreaking 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, cultural anthropologist Joseph Campbell argues that the world’s great myths and creation stories follow the same basic plot:

Life in the village is normal until one day an urgent problem arises—such as a menacing dragon. A hero accepts the challenge and goes on a quest to find and slay the dragon. Obstacles arise along the way, and the hero considers giving up. But in a moment of insight, the hero realizes what must be done to succeed. Our hero musters the resolve to slay the dragon and returns home triumphant, with new knowledge and experience. Order is restored.

Of course, it’s not always a dragon. Sometimes the challenge is more personal or spiritual, such as a quest for self-knowledge or enlightenment. But the basic journey is there: a call to adventure, mounting difficulties, a moment of insight, climactic action, order restored.

Master storytellers use structure—or the strategic ordering of events—to propel a story forward. The underlying structure may go unnoticed by listeners or readers who are wrapped up in the drama. But a well-structured story taps into audience expectations and stokes anticipation. It’s the same for speech stories. We just have less time to get to the point—minutes, not hours.

In its most basic form, story structure involves a hero, a complication, and a resolution. And the “hero” is often you, the speaker. In addition, you should make the connection between the hero’s journey and why it’s relevant to the audience (more on that later).

Complication-Resolution Structure

The order in which you present the narrative—complication, then resolution—is critical, because the complication grabs the listeners’ attention and makes them eager to find out what happens next. They want to learn vicariously from others’ mistakes and avoid the same pitfalls—or follow the footsteps of a successful mission.

Building on the complication-resolution foundation, Hollywood screenwriter Robert McKee, an expert on structuring film scripts, explains additional elements in his book Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting. These include:

1 Setup.

Describe the hero/main character in a life-as-usual setting. Provide a few key details to help the audience relate, but don’t spend too much time here. You need to get to the action or risk losing attention.

2 Inciting incident.

Describe the urgent problem that throws life out of balance for the hero. It can be something external, like getting a flat tire on a busy highway. Or it could be internal, like the realization that you’re no longer happy in your career. The inciting incident generally comes early in the story, to hook the audience. It kicks off the journey.

3 Progressive complications.

The hero’s first attempt to “slay the dragon” may not succeed, which means they must try harder. Describe additional problems that crop up, whether external or internal (self-doubt, for example). Progressive complications hold the audience’s attention, as they wonder how the hero will pull through.

4 Insight.

Describe the breakthrough moment when the hero realizes what must be done to achieve success or to reach a new level of being. This insight informs the hero’s next action.

5 Climax and resolution.

Slay the dragon. Describe the action that finally brings the journey to an end and restores equilibrium in the hero’s life.

6 Lesson.

In a film or novel, the lesson may be left to the audience’s interpretation. In a speech, we state it explicitly and relate it to the audience.

A Toastmaster’s Tale

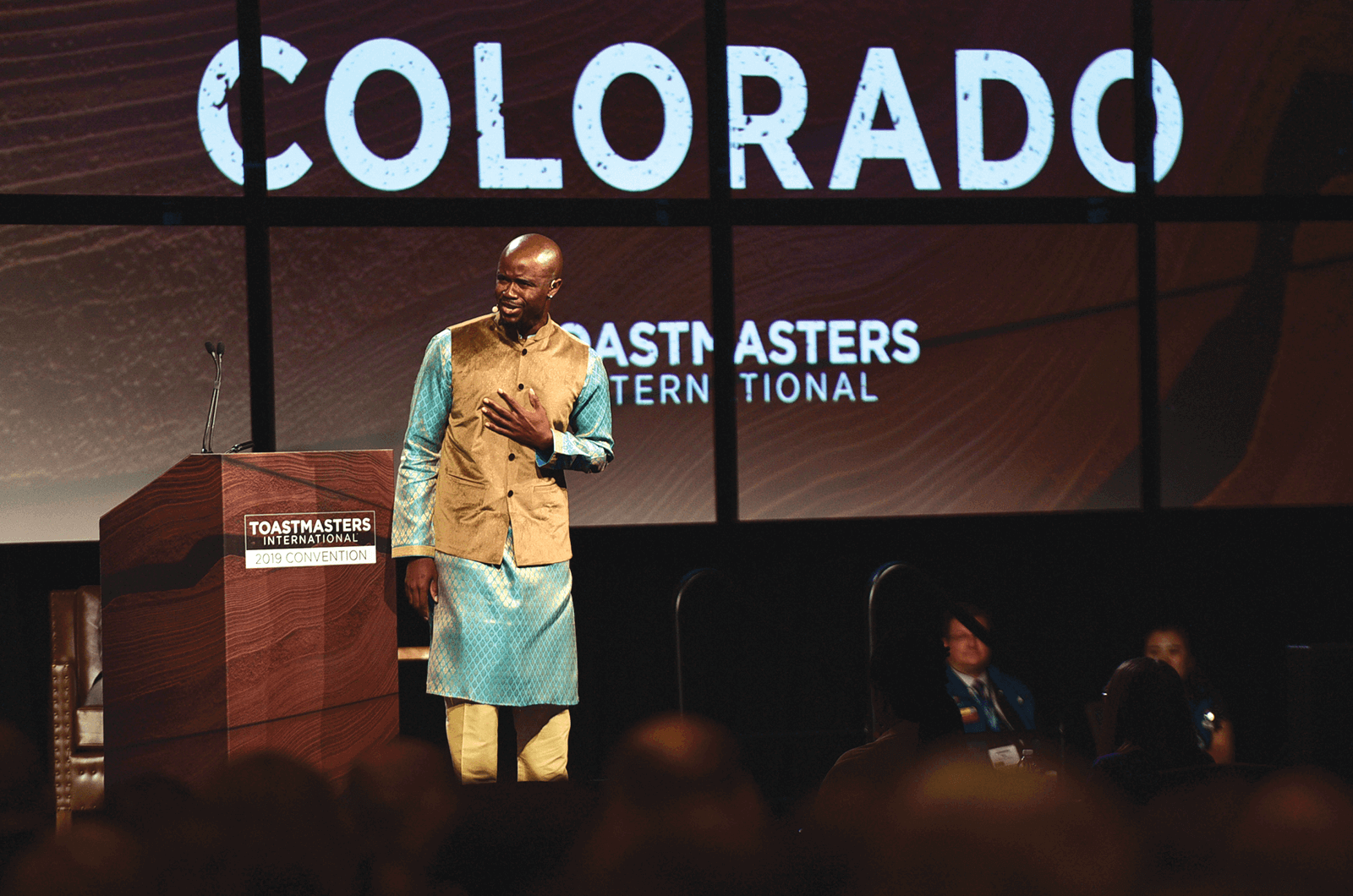

Aaron Beverly masterfully used these elements at the 2019 World Championship of Public Speaking® in his winning speech, An Unbelievable Story.

Beverly quickly set up the dramatic possibilities by reliving his experience at the wedding of dear friends, from both Indian and white families. Beverly, who noted he was the only black man at the festivities, enthusiastically donned the traditional attire for an Indian wedding (which he wore while delivering the speech).

Conflict and humor ensue as Beverly accepts the critical mission of protecting the groom’s shoes from bridesmaids determined to steal them. If he failed, Beverly noted, the groom would pay a healthy ransom for his footwear.

He is certain of his success, noting over and over that he takes the mission very seriously. However, a number of obstacles are thrown his way, as the bridesmaids try many clever tricks to fool him into giving up the shoes. He manages to fend off every wily attempt until at last he is outnumbered by additional members of the wedding party, and the shoes are wrested from his grasp.

Beverly moves here into insight, resolution, and a lesson. “The context behind the game,” he noted, “was really to help the families get to know one another better” and to welcome him into the culture and festivities of the day. He learned that open hearts and open cultures help us avoid the “impossible stories” that doom so many human relationships.

He asks the audience to practice “acceptance despite difference.” His final call to action: “This is your mission—and I ask you to take it very seriously.” Applause, cheers, championship.

Authenticity and Relevance

Core storytelling elements create even more spellbinding stories when applied to tales of personal experience—the most original content we can offer. Audiences crave first-hand accounts. They want to hear observations and insights from someone who lived through an experience. When we share openly, we show our humanity and allow the audience to identify with us.

The late Apple Computer founder Steve Jobs used these techniques in his 2005 commencement address at Stanford University, with the story of his painful yet invaluable self-discovery following being fired from the company he built. (See page 19 for an analysis.)

Unless the goal is mere entertainment, speech stories must have a purpose. Likewise, we should all be clear about our purpose and frame our stories for audience consumption. That means explicitly stating the lesson and relating it to the audience, a storytelling action that Toastmasters practice regularly, from the club to world championship levels.

I began this piece by describing a scene from A Star Is Born about an unknown singer who achieves success beyond her wildest dreams. My purpose? To illustrate the value of familiar patterns in stories. A Star Is Born is a story with wide appeal; we all want to have our talents recognized and be seen for who we are.

In your next speech, show your talent with a well-told story. Watch the audience lean in.

Learn additional storytelling tips in the video below from Toastmaster and educator Erin Gruwell.

Jesse Scinto, MS, DTM is a Fulbright scholar and deputy director of the strategic communication program at Columbia University in New York City. He’s also the founder/CEO of Public Sphere, a leadership communication firm, and a member of Greenspeakers Club in New York City.

Previous

Previous

TAKE YOUR STORIES ALONG IN PATHWAYS

TAKE YOUR STORIES ALONG IN PATHWAYS

Previous Article

Previous Article